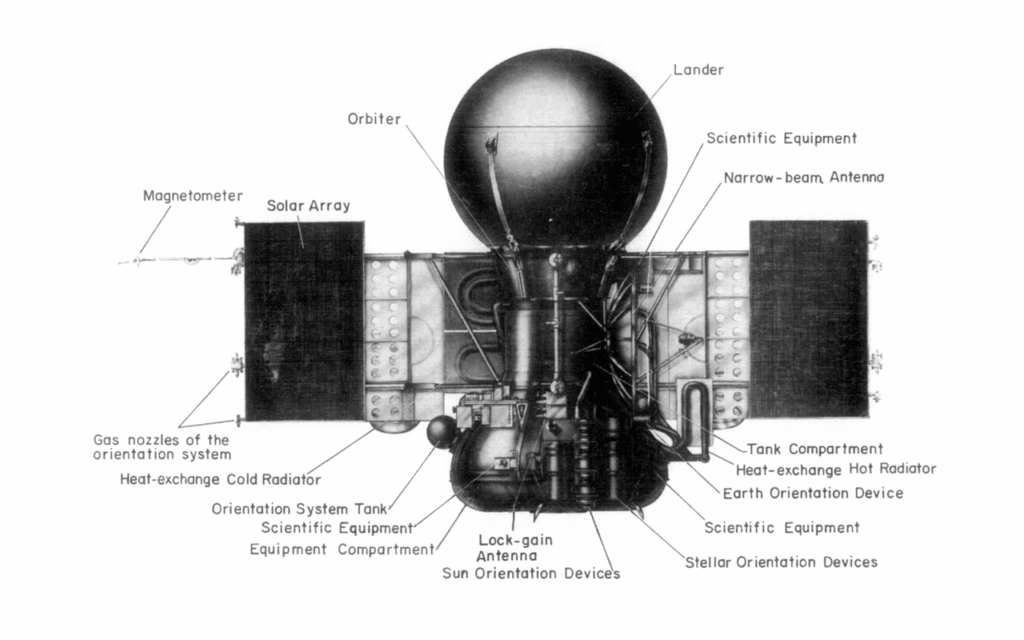

On October 20, 1975, 134 days after its June 8 launch from Baikonur Cosmodrome, the Soviet space probe Venera 9 approached to within 1600 km of the surface of the planet Venus. The probe released its principal payload, a 2.4 m diameter aluminum sphere containing a 2 m, 660 kg surface lander. The spacecraft bus (2.8 m, 3500 kg), carrying the probe’s propulsion system and fuel supply, solar array, antennae, control systems, and instrumentation, made two brief orbit insertion burns, achieving an eccentric 1510 × 112,200 km orbit of Venus on October 22, becoming the planet’s first artificial satellite.

The Venera 9 probe. (Image source: Keldysh 1977)

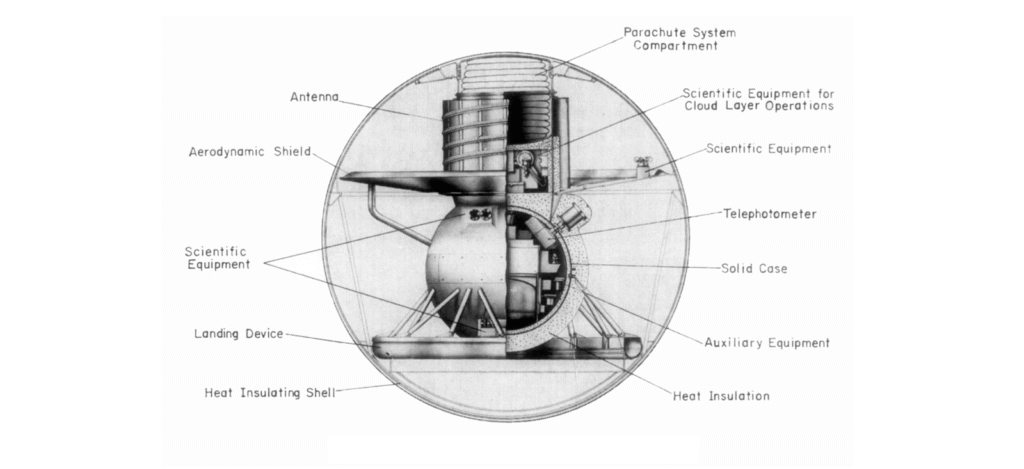

Two days after its release, the insulating sphere began its ballistic descent to the surface at an initial velocity of 10.7 km/sec. As it fell through the raging cloud layers – comprised mostly of sulfuric acid, with wind speeds in excess of 360 km/hr – aerodynamic deceleration slowed the sphere’s velocity to 250 m/sec. At an altitude of 65 km, the parachute compartment opened and a series of drogue, extraction, and decelerating parachutes carried away the sphere’s upper half and slowed the descent to 50 m/sec. The lander’s onboard radio activated and began transmitting data to the orbiter. At an altitude of 62 km, the sphere’s lower half was jettisoned and three large canopy parachutes deployed. Tethered to the parachutes, the now fully-revealed lander descended through the remaining cloud layers for another 20 minutes, while its instruments measured atmospheric composition, wind speed, and photometry. After exiting the clouds at an altitude of 50 km, the parachutes released and the aerodynamic brake, a 2 m disc encircling the lander’s housing, provided resistance to the increasingly dense atmosphere, slowing it to a terminal velocity of 7 m/sec. On impact, the shock-absorbing landing gear crushed against the profile of the uneven terrain, as it had been designed to do so as to anchor the lander in an upright position.

The Venera 9 lander. (Image source: Keldysh 1977)

The Venera 9 lander touched down on Venus at 05:13 UTC, on October 22, 1975, at the base of a hill in Beta Regio, an upland volcanic rise in the planet’s northern hemisphere. The sun was near its zenith and visibility on the surface was about the same as on an overcast day in Gainesville. The anemometer recorded a light breeze – albeit of supercritical carbon dioxide – between 0.4 and 0.7 m/sec. Atmospheric pressure was measured at 90 bar, roughly the pressure felt 900 m underwater on Earth. The surface temperature was 455° C (851° F).

Two minutes after touchdown, the protective cap on the lens of one of the lander’s two optical-mechanical cameras was successfully released – the second cap failed to release – and the lander began recording this photograph of the site…

The Venera 9 landing site, October 22, 1975. (Image source: Russian Academy of Sciences)

Over the course of thirty minutes the camera scanned a left-to-right, 115 × 512 pixels, 174° panorama, then reversed direction and began scanning the same terrain a second time. The image data and other instrument telemetry were sent in real time to the orbiter, which then relayed them to Earth, the first time an orbiter had been used in this way.

Because the lander had come to rest on an incline of about 20°, the camera was able to capture a portion of the horizon (as much as 100 meters away) and the sky in the upper right and left corners of the image. The blurred object on the lower right, the gray and white arc on the bottom, and the device that resembles a paint roller or a squeegee, are parts of the lander. The image is dominated by well-lit layers of flat, sharp-edged stones – most a few tens of centimeters across and in thickness, but some much larger – interspersed with finely grained regolith, suggesting a geologically young and dynamic terrain. (Perhaps the landing site is the debris-strewn slope of a lava dome?) It seems an unremarkable image of a scree littered with rockfall. Until you remember that it’s a scree… on Venus.

This extraordinary photograph, the first ever taken from the surface of another planet, combines in its peculiar way the marvel and the mundanity of such moments in planetary exploration. In 1975, what could be more outré than sending a 5 watt camera 360 million kilometers away, to one of the most brutal, hostile environments in the solar system, expecting it to take and send back a decent snapshot? And what could be more ordinary, more commonplace on the ancient surface of our sister planet than a heap of stones on a hillside, minding their business under a still, empty, and marginally sunny sky?

Fifty-three minutes after touchdown, as the camera completed 124° of its right-to-left pass, all data transmissions from the lander ended when the orbiter moved out of radio range. (And, not, as is often claimed, because of rising temperatures within the lander.) The Venera 9 orbiter would continue to gather and transmit data on Venus’ atmosphere, ionosphere, and surface for another three months, until its transmitter failed. The mission was officially ended on March 26, 1976.

Communications with the Venera 9 lander were never reestablished.

– Terry Harpold, Assistant Director, Astraeus Space Institute

Selected Bibliography

Harvey, B. (2007). Russian Planetary Exploration: History, Development, Legacy, Prospects. Springer.

Keldysh, M. V. (1977). “Venus Exploration with the Venera 9 and Venera 10 Spacecraft.” Icarus, 30, 605–625.

Mitchell, D.P. (2004). “Venera: The Soviet Exploration of Venus.” http://mentallandscape.com

Siddiqi, A.A. (2018). Beyond Earth: A Chronicle of Deep Space Exploration, 1958–2016 (2nd ed.). National Aeronautics and Space Administration.