As the clock approached 10 AM EST on the morning of October 25, 1965, the crew of Gemini VI, Commander Walter M. “Wally” Schirra (1923–2007) and Pilot Thomas P. Stafford (1930–2024), suited and sealed in their spacecraft atop the two-stage Titan II launch vehicle on Cape Kennedy’s launchpad 19, were preparing for liftoff. Eighteen hundred meters away, on launchpad 14, the uncrewed Agena Target Vehicle (ATV), a newly-redesigned version of Lockheed Aircraft’s Agena-D upper stage rocket—a veteran of more than 140 military reconnaissance missions—sat atop an Atlas first stage. At 10 AM, the go for the Atlas-Agena launch was given and the spacecraft rocketed skyward, headed for Earth orbit. Six minutes later, air-to-ground telemetry with the ATV was lost; Air Force radar indicated that the spacecraft had broken into five pieces. Fifty minutes in, radar tracking from Carnarvon, Australia, confirmed that Atlas-Agena had exploded shortly after the first stage burn, at about 217 km above the Earth’s surface. The literal target of their mission now gone, the Gemini VI launch was scrubbed and Schirra and Stafford were escorted from the spacecraft.

The modifications made to the new Agena design had included the addition of guidance and radar hardware, running lights, a restartable engine, and a docking collar designed by McDonnell Aircraft. Had the Atlas-Agena launch gone as planned, Gemini-Titan would have lifted off 101 minutes later, as the ATV passed again over Kennedy, giving chase. Six hours and four orbits after that, the crewed spacecraft would have caught up to the ATV and, over the course of the two-day, 29-orbit mission, would have attempted to dock with its target four times, proving that human-piloted orbital rendezvous and docking were possible.

Orbital operations of this sort had been fundamental goals of astronautics since the field’s inception. Pioneering figures such as Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857–1935), Yuri Kondratyuk (1897–1942), Hermann Oberth (1894–1989), and Wernher von Braun (1912–1977) had long argued that long space voyages like a trip to the moon and back could be best accomplished with intermediate orbital phases and function-specific, modular spacecraft. Rather than relying on a gigantic launch vehicle to lift a single, large spacecraft that would travel directly to the moon and land with enough fuel still on board for a self-powered return to Earth—the so-called “direct ascent” method—a more flexible and fuel-efficient solution, they observed, would be to assemble modules with distinct command and landing functions in orbit, and to discard them when their roles in the mission were completed. (This would be the approach of the Apollo missions, which adopted Kondratyuk’s 1919 lunar orbital rendezvous scheme involving a separate Lunar Excursion Module ferried to the moon by a Command Module and left behind after successful descent and ascent.) Initial American and Soviet plans for crewed lunar missions were predicated on the assumption that the voyage would be by direct ascent. Supporters of that approach resisted Earth and lunar orbital rendezvous as too complex and risky. But by the early 1960s it had become clear inside NASA that direct ascent would require a costly new generation of super heavy-lift launch vehicles that could not be ready for a lunar landing before the end of the decade, the deadline to which President John F. Kennedy had committed NASA in September 1962.

To assemble modular spacecraft in orbit, a pilot must be able to fly the chase vehicle in close formation with its target, taking into account counter-intuitive nuances of orbital mechanics while the vehicles are moving independently, in the case of the Apollo missions at projected velocities of between 1.7 km/s (lunar orbit) and 7.8 km/s (Earth orbit); even a minor uncontrolled bump between the vehicles could have catastrophic consequences. In December 1965 orbital operations of this precision had never been completed. In 1962 and 1963 the Soviets had launched pairs of crewed spacecraft (Vostok 3 and 4, Vostok 5 and 6, respectively), inserted them into nearly identical orbits and guided them as close as then feasible: within radio and visual range of one another but no nearer than 5 km apart. NASA’s first attempt at rendezvous in June 1965, when Gemini IV’s Commander Jim McDivitt (1929–2022) tried to maneuver the spacecraft close to the spent Titan II’s upper stage, had failed because he had not been trained in orbital guidance techniques.1 The loss of Atlas-Agena would force a postponement of Gemini VI’s better-prepared rendezvous and docking trials by at least half a year, while Lockheed built another ATV and NASA tested and certified the vehicle for flight.

Within the first few hours following the scrubbing of the Gemini VI mission, a small group of engineers and flight planners began working on the details of a bold alternative plan. The next crewed mission, Gemini VII, commanded by Frank Borman (1928–2023) and piloted by James Lovell, Jr. (1928–2025), was scheduled to lift off in two months, on December 4. During its 14-day, 224 orbit mission, at the time the longest spaceflight ever attempted, Borman and Lovell would be subjected to a taxing series of medical experiments to determine effects of close confinement and microgravity on astronauts’ physiology. Because Gemini VII would remain aloft and in a fixed orbit for a full two weeks, the upstart group proposed that the spacecraft could serve as the passive target for Gemini VI’s rendezvous trials. Docking would not be possible but orbital operations could be practiced in advance of future missions involving the ATV. The logistics involved were daunting: Gemini VII and VI must lift off from launchpad 19 not much more than one week apart. The rapid turnaround would still require needed repairs to portions of the launch complex blasted by the Gemini VII liftoff, assembling the GLV-6 Titan II on the launchpad and mating it with the Gemini VI capsule, and running diagnostic checks on all systems to verify mission readiness—all mission-critical procedures that before had taken several weeks to complete—but a comparable window of opportunity in which to rendezvous two crewed missions in orbit would not be repeated in either Gemini or Apollo.2 After two days of running through variations on this scenario and sometimes contentious discussion within and between mission teams in Houston, Huntsville, and Cape Kennedy, the plan to launch VII and VI in quick succession and attempt rendezvous was approved by Manned Spacecraft Center Director Robert Rowe Gilruth (1913–2000) and NASA Administrator James Edwin Webb (1906–1992). On October 28 the plan was announced to the public.

On December 4, 1965, at 2:30 PM EST, Gemini VII was launched into orbit without incident. After four minor course adjustments, Borman and Lovell’s spacecraft entered a nearly circular orbit of approximately 300 km, close to the planned orbit of the lost ATV. Eleven days later, on December 15, at 8:37 AM, the newly-christened Gemini VI-A successfully lifted off in pursuit of its target.3 As they passed over Tanarive, Malagasy Republic, the Gemini VII crew spotted VI-A’s contrail and briefly the spacecraft itself. For the first time in history, four humans were in space at the same time. Borman and Lovell suited up and prepared for visitors.

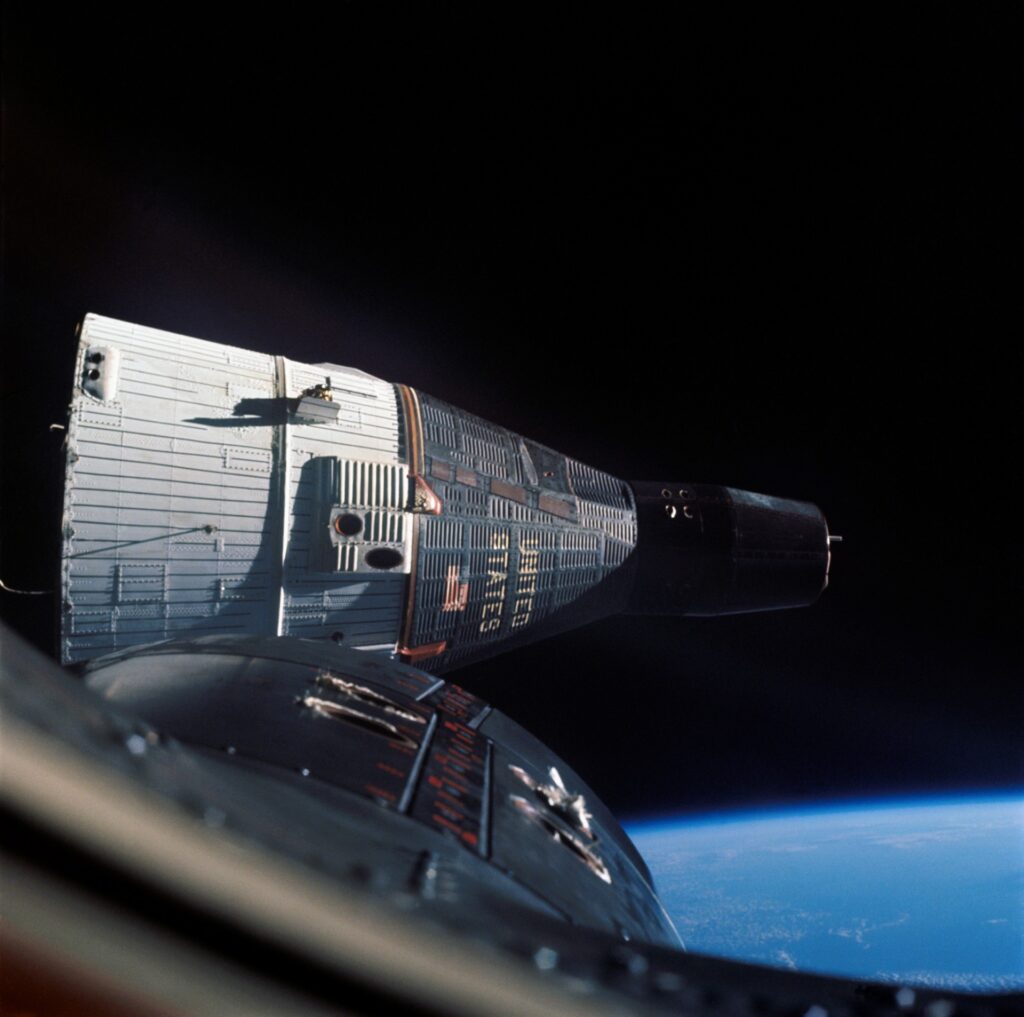

At orbital insertion, Gemini VI-A trailed its target by about 2000 kilometers. Over the course of four orbits, Schirra repeatedly fired the vehicle’s forward and aft thrusters, making small adjustments to its speed, apogee, perigee, and orientation, bringing it closer to Gemini VII. Five hours and 4 minutes into the mission, VII could be seen from VI-A, a point of reflected sunlight 100 kilometers away. At five hours and 50 minutes, the two spacecraft were 900 meters apart, and VI-A began its braking approach. At 2:33 PM EST, December 15, 1965, VI-A and VII were forty meters apart, traveling at the same velocity in a synchronized position known as stationkeeping. Flight controllers in Mission Control erupted into cheers, waving small American flags and passing out cigars. Schirra, Stafford, Borman, and Lovell pressed their faces to the inside of the portholes of their respective spacecraft, grinning widely at one another. Successful rendezvous had been achieved.

For the next three and a half orbits, VII remained in a fixed relative position while VI-A circled it with balletic grace, moving out as far as 90 meters and in as close as 0.3 meters, playing with different approach velocities and orientations, several times holding to a stationkeeping position for as long as 20 minutes without the pilot touching the steering handle. When it came time for Borman and Lovell to perform one of their medical experiments, Schirra moved VI-A to a discreet 12 meters away and parked for a time. As sunlight shone brightly through one or the other VI-A porthole, Schirra and Stafford traded navigational control, both amazed at the precision of the spacecraft’s handling; once rendezvous had been mastered, they concluded, orbital docking would be a cinch.4 When the scheduled sleep period arrived, Schirra moved VI-A to a distance of 16 km and parked before both crews settled in for the night.

The next morning, as Borman and Lovell prepared to resume the daily grind of their exhausting mission, and Schirra and Stafford prepared to leave orbit, Stafford surprised Gemini VII and ground control with an unexpected radio transmission:

We have an object. It looks like a satellite going from north to south, up in a polar orbit. He’s in a very low trajectory, traveling from north to south. It has a very high [fineness] ratio. It looks like it might be [inaudible]. It’s very low; it looks like he might be going to re-enter soon. Stand by, One. It looks like he’s trying to signal us…

Over “One,” the joint mission communications circuit, Schirra and Stafford could be heard playing a few bars of “Jingle Bells,” Schirra on a Hohner “Little Lady” four hole harmonica and Stafford shaking a cord strung with six bells, both of which had been smuggled onto VI-A before liftoff: the first ever live musical performance in space.

With all assured that Santa Claus was safely on his way, Schirra closed the transmission with, “Really a good job, Frank and Jim, we’ll see you on the beach,” fired thrusters to put a little more distance between the VI-A and VII, and began to ready his spacecraft for descent. On December 16, 1965, at 10:29 AM EST, Gemini VI-A splashed down in the West Atlantic, about 13 km from its planned impact point. Their arrival was broadcast in real time via satellite from the recovery ship USS Wasp (CVS-18), the first live global transmission of a spacecraft returning to Earth. Two days later, on December 18, at 9:05 AM EST, Gemini VII splashed down in the Atlantic southwest of Bermuda, about 10 km from its planned impact point. Their arrival was also broadcast globally in real time from the USS Wasp.

Today, the Gemini VI-A and VII capsules can be viewed at the Stafford Air and Space Museum in Weatherford, Oklahoma, and the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia. Schirra’s and Stafford’s harmonica and bells are on display in the National Air and Space Museum’s main complex in Washington, D.C.

– Terry Harpold, Assistant Director, Astraeus Space Institute

Notes

1Line-of-sight techniques that accounted for orbital dynamics were the subject of Edwin Eugene “Buzz” Aldrin, Jr.’s (b. 1930) 1963 MIT PhD thesis in astronautics. The thesis earned him the nickname among fellow astronauts of “Dr. Rendezvous,” and would become the basis of NASA’s future orbital rendezvous techniques. Aldrin would himself put them into practice as the pilot of Gemini XII (1966) and Eagle, the Lunar Excursion Module of the Apollo 11 moon landing (1969).

2In fact, Gemini VII would hold the record for the longest crewed space mission until Soyuz 9 (June 1970), and the longest mission in U.S. history until Skylab 2 (May–June 1973).

3The December 15 take-off was the second attempt to place Gemini VI-A into orbit. A December 12 launch had been scrubbed following a momentarily frightening shutdown of the launch vehicle a few seconds after engine ignition. In a remarkable demonstration of sangfroid, Schirra and Stafford declined to eject the capsule, as per mission protocol, because they had not felt the sudden jolt of upward motion that would have indicated that the Titan II was at risk of falling over and exploding in a massive fireball. In a hurried, overnight inspection of the rocket it was discovered that a small dust cover, no larger than a nickel, had been accidentally left in place on a check valve of the engine’s gas generator during routine maintenance months before. The resulting valve failure had provoked the emergency shutdown. A few engine parts were cleaned and replaced and the vehicle was certified for liftoff.

4The next attempt to dock with the ATV would be during the March 1966 Gemini VIII mission, commanded by Neil Armstrong (1930–2002) and piloted by David Scott (b. 1932). In addition to rendezvousing with the ATV, the three-day mission was to have included a spacewalk by Scott and several scientific and medical experiments. But soon after a successful docking procedure, Gemini VIII lost attitude control due to a malfunctioning thruster and the combined vehicle began to tumble uncontrollably. Out of range of ground communications at the time, Amstrong and Scott quickly improvised a solution using the spacecraft’s thrusters to undock from the ATV and regained control of the spacecraft by firing its Reentry Control System to slow and stop the tumble. As per mission protocol after such an emergency—the first critical in-space failure of a U.S. spacecraft—Gemini VIII returned to Earth after its next orbit and safely splashed down off the coast of Japan.

Selected Bibliography

Aldrin, E. E., Jr. (1963). Line-of-Sight Guidance Techniques for Manned Orbital Rendezvous. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Brooks, C. G., Grimwood, J. M., & Swenson, L. S., Jr. (1979). Chariots for Apollo: A History of Manned Lunar Spacecraft. National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Grimwood, J. M., et al. (1969). Project Gemini: Technology and Operations, A Chronology. National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Hacker, B. C., and Grimwood, J. M. (1977). On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini. National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Kluger, J. (2025). Gemini: Stepping Stone to the Moon, the Untold Story. St. Martin’s Press.